Soldiers appeared on Benin's state television on December 7, 2025, announcing the dissolution of the government and the removal of President Patrice Talon, who had been in power since 2016. The group, calling itself the Military Committee for Refoundation, named Lieutenant Colonel Pascal Tigri as its president and immediately closed the country's borders while declaring all state institutions dissolved. Reports from Cotonou indicate gunfire near Camp Guézo by the presidential residence, with the French embassy issuing shelter-in-place warnings to its nationals as troop movements were observed around strategic points in the capital.

The apparent coup transforms Benin from a coastal reform success story into the latest West African state to join a regional pattern that has seen eight military takeovers since 2020. What makes this move particularly significant is its timing: Talon had publicly committed to stepping down after the April 2026 presidential election, with his ruling coalition already nominating Finance Minister Romuald Wadagni as a successor. His intended exit stood out in a region where leaders routinely manipulate constitutions to extend their tenure—making the decision to oust him via military force, rather than through an electoral process already in motion, a revealing choice about the drivers behind this intervention.

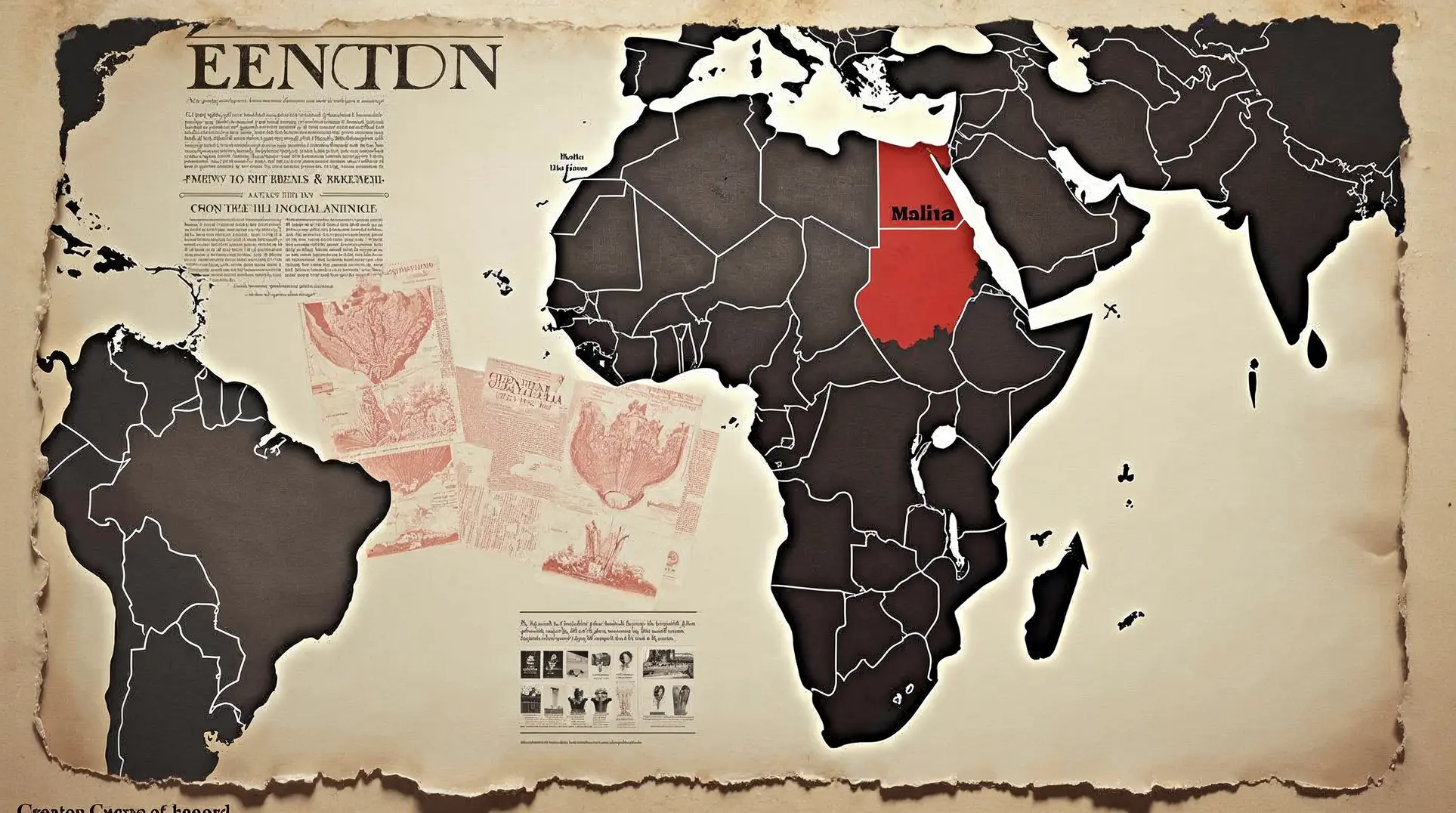

From Sahel core to Atlantic coast

Benin's apparent putsch marks a geographic shift in West Africa's coup contagion. Since 2020, military takeovers in Mali, Burkina Faso (twice), Niger, Guinea, Chad, Sudan, and Gabon have concentrated in Sahel states facing acute jihadist violence or extractive post-colonial governance failures. Guinea-Bissau's recent military seizure of power extended the pattern to a coastal state, and now Benin—a country long marketed by international financial institutions as a model of democratic consolidation and economic reform—joins that list.

The Committee's chosen name—"Refoundation"—echoes the language deployed by juntas across the Sahel, where military actors frame their interventions as existential corrections to broken social contracts rather than mere power grabs. Whether Benin's putschists adopt the familiar script—promising brief transitions, anti-corruption drives, and sovereignty rhetoric against external interference—will become clear in the coming days. Early indications suggest they are following the playbook: border closures to control information and movement, dissolution of civilian institutions, and appointment of a military leadership structure.

Northern Benin has experienced growing jihadist spillover in recent years, with al-Qaeda affiliate JNIM claiming attacks in the region as the group extends its operational reach southward from core Sahelian theaters. While it remains unclear whether security grievances drove the military's move, the Committee will likely invoke threats to national integrity as part of its justification narrative—a pattern seen in Burkina Faso and Mali, where juntas leveraged genuine security crises to consolidate legitimacy even as their own performance against armed groups remained mixed.

Members are reading: How ECOWAS's eroded credibility and internal contradictions make Benin the critical test of regional institutions' relevance.

What comes next for Benin and the region

Benin's apparent coup arrives at a moment when West African publics are increasingly skeptical that electoral processes deliver security or livelihoods. Talon's tenure saw economic growth figures that satisfied international lenders but also witnessed persistent complaints about authoritarian drift, with high-profile prosecutions of opponents framed as anti-coup measures. Whether the Military Committee for Refoundation can translate dissatisfaction with civilian governance into durable legitimacy remains uncertain—most Sahelian juntas have struggled to improve security or economic outcomes even as they tighten political control.

The immediate focus must be on preventing violence. If military factions fragment or if loyalist forces mount resistance, Cotonou could descend into armed confrontation. Talon's whereabouts and condition remain unreported by credible sources, and the fate of senior government officials will signal whether this takeover seeks managed transition or wholesale purge. International actors, particularly France and the United States, will face difficult choices about engagement: outright isolation risks pushing Benin toward the Sahelian model of Russian partnership, while premature normalization rewards unconstitutional power seizures.

Benin's putsch transforms a regional trend into a structural crisis. When coups migrate from conflict zones to coastal states preparing for democratic transitions, the question is no longer whether West Africa's institutions can manage isolated shocks—it is whether they retain any capacity to enforce constitutional norms at all.

Subscribe to our free newsletter to unlock direct links to all sources used in this article.

We believe you deserve to verify everything we write. That's why we meticulously document every source.